EEJOON CHOI / NEXTGENRADIO

What is the meaning of

home?

Lolita Mojica speaks with Anthony Ammons who has searched his whole life to find a sense of home within his surroundings, which led him down a dark path, leading to his incarceration. After having his sentence commuted, he has made self work and advocacy his mission, focusing on helping others overcome their past struggles, just as he did.

A New Purpose, and Home, Following Life in Prison

The story you’re about to hear contains a description of a violent act, and the language may be upsetting to some listeners.

Listen to the Story

Click here for audio transcript

Anthony Ammons Jr.:

I grew up in a place, the environment as a whole was unstable. The outside entities was filled with gangs.

Hi, my name is Anthony Ammons, Jr.

I felt very unseen and very unheard. I was trying to be seen by my mom and my dad. In the house … I didn’t feel it was a home. It was more so of a house.

I started to gangbang at an early age. I started to hang out. I started to run the streets. I started to not care.

All along, I was suffering from an identity issue, a self-esteem issue, a low self-worth issue. So violence, in a sense, filled the void of my loneliness.

All I cared about at 16 years old was an image. My identity was in my gang, it wasn’t in myself.

March 31st, 2001, I was driving down the street in a Bronco with two co-defendants. As we drove down Crenshaw Boulevard, we pulled alongside of a cherry-red Caprice.

I yelled out the car, “What’s up blood?”

He did not hear me, which angered me. And then, I reached out the car and I shot into his car, missing the driver, hitting the passenger in the head, and then shot again to kill the other person.

And all of this was in order to seek approval that I was down. I was tough. I was hard … which all equals to be seen.

I didn’t understand that 102 years to life actually equals to I’m not getting out of prison till 2103.

After the sentencing, the first night was the loneliness. It wasn’t, it wasn’t a sleepful night. It was a teary-eyed night.

I actually got to San Quentin on an adverse transfer, which means I got in trouble and got kicked out of a prison to get to that prison.

I always say this: it wasn’t the prison that changed my life, it was the men. I started playing basketball immediately once I got there and it was just so fun.

The basketball court was my first home. My team meant everything to me. They were, they were more than just my brothers.

I worked towards my healing, I realized that I suffered trauma. So, I had to take that on and say no matter what, I have to install good.

By 2015, I realized that I had an opportunity to possibly go home. Governor Brown reduced my sentence from 102 years to 19 years to life.

So, the day that I was released from prison, that was the bittersweet moment that I left my team behind. When I left, I felt that I was leaving a part of me with them.

Currently, I work for a couple of nonprofit agencies: One of them dealing with youth in West Oakland, um, and then I also work for the Department of Justice as a special projects coordinator, and I also worked for a company called ReEvolution to where I go into the prisons and teach youth mentorship.

The work that I’ve been doing will never stop; Nothing will ever stop it but death. My whole goal at the end of the day is to see if I can get there, who else can? So, I’m the first but can’t be the last.

Unfortunately, after my release, I was shot. What being shot did do to me, it gave me a greater sense of empathy. Because when I got shot, all I could think of was, “Wow … I get it.” So for me, being shot only intensifies the work.

Every morning, I wake up at 4 o’clock, pray and then, uh, say 2103. Because that was my earliest parole hearing.

Anthony Ammons Jr. (Left) embraces his mother, Shelly Warren, while on a visit to her home in Compton, Calif., on March 11, 2024. Warren wrote to her son every week of the 20 years he was incarcerated.

LOLITA MOJICA / NEXTGENRADIO

Cigarette smoke lingers in a small living room, lined with family photos, some of them askew. Keepsakes from birthdays, baby showers and graduations are scattered throughout the space, some spilling out from under a coffee table. Trophies and family photos collect dust on a side table by a window in the corner.

“My mom keeps everything,” Anthony Ammons said with a laugh.

In his early childhood, Anthony was a bright-eyed kid with big hoop dreams. The basketball court was where he felt most at home.

However, as Anthony got older, his home life became increasingly unstable. His father was absent for most of his life, choosing the street life over his. Anthony recalls witnessing abuse and carrying the knowledge that his mother was suffering from addiction. As his sense of safety grew dwindled, Anthony felt unseen and unheard, longing for a sense of comfort.

“I started to not care,” Anthony said. “I was suffering from an issue of loneliness … violence, in a sense, filled the void of my loneliness.”

Anthony seemingly found acceptance and understanding when he joined a gang. With each crime he committed, he found acceptance from his peers.

Things came to a head in March 2001. Anthony recalled cruising around with two friends. They pulled up to a car at a red light and began to heckle the occupants.

Citing a desire to impress his friends, that was when he fired several shots, striking two of the car’s passengers — killing one of them.

Following the shooting, Anthony was given a sentence of 102 years to life, the severity of which did not sink in until he spent his first night in prison and felt the sting of loneliness.

Anthony eventually found himself at San Quentin State Prison, following dismissal from a maximum security prison. He soon joined the prison’s basketball team, sponsored by the Golden State Warriors.

“It was just so fun to play with guys, especially at a level that I knew how to play at … a level that requires accountability,” Anthony said.

Being part of the team gave Anthony a reason to follow protocol and focus on his personal development.

Shelly wrote him letters every week for the 20 years that he was incarcerated. With each letter, their relationship evolved and she began to change.

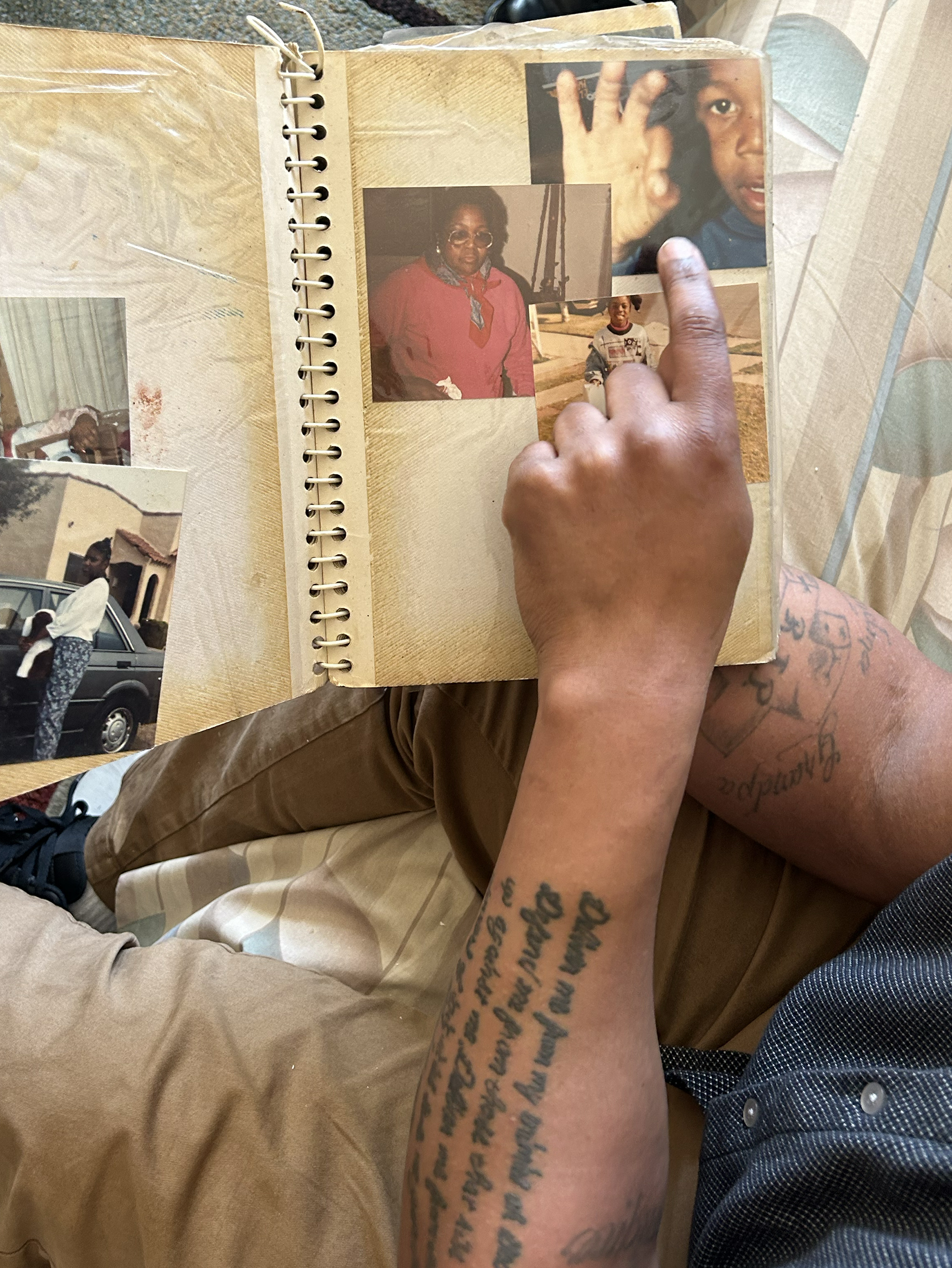

In one letter, dated September 2003, Anthony’s mom spoke hopefully. She told her son about her new job and a new home and celebrated her sobriety and her faith in God. Anthony beamed with pride when reading her letter aloud.

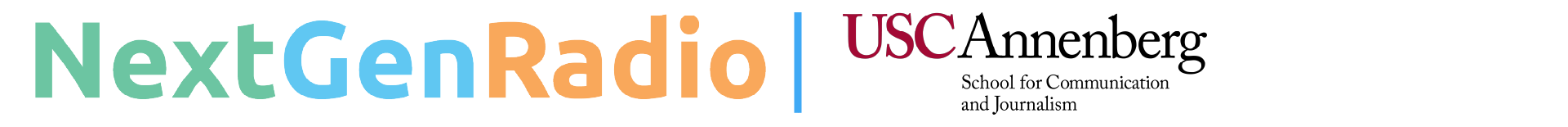

Anthony Ammons looks through one of the many photo albums at his mother’s house. He lingers on a photo of himself, at about age 8. “That’s me throwing up gang signs early,” he laughs.

LOLITA MOJICA / NEXTGENRADIO

Anthony Ammons reads one of the letters his mom wrote to him in prison. One of her letters, dated September 2003, starts with, “Dear Anthony, How’s mommies [sic] baby doing?”

LOLITA MOJICA / NEXTGENRADIO

Click here for audio transcript

I always say this: It wasn’t the prison that changed my life, it was the men. I started playing basketball immediately once I got there and it was just so fun.

I’m emotionally naked on a basketball court, if that makes sense. Game days at San Quentin are so awesome. I mean, you go out there, you got guys sweeping off the courts. We have referees, we have managers, we have clock guys that run the clock, and we have the team.

I usually used to get out there a little earlier, um, to shoot free throws because I was horrible at free throw shooting, because I have all this anxiety inside my body before any game. Even though I love basketball and I play it a lot, before any game, I get anxiety. I get butterflies in my stomach until tip off.

My team meant everything to me. They were, they were more than just my brothers because what I learned that, what I learned about a friend and a brother is that no matter the struggle you’re held accountable.

“Getting these letters from my mom … I felt like a son,” Anthony said. “I felt seen. I felt heard. Even though it was a separation, I felt wanted, loved.”

While he was in prison, Ammons’ mother made the effort to make him feel included in family celebrations by photoshopping him into photos. A Christmas card features the family posing together with Ammons, dressed in his prison uniform, lingering in the background.

LOLITA MOJICA / NEXTGENRADIO

After leaving prison, Anthony was introduced to California Assemblymember Mia Bonta (D-Oakland). Bonta’s husband, California Attorney General Rob Bonta, hired him soon after.

Under Bonta, Anthony said he drew from his experiences to develop solutions for the community and life after prison.

Today, he says his purpose is to bring awareness to the struggles formerly incarcerated people face upon their reentry into society.

Anthony said there are many things that formerly incarcerated people cannot do, which may surprise people.

“In the state of California, there are certain things that you can’t do having a record,” Anthony said.

“Getting pulled over sucks because immediately, when you’re on parole, you get your car searched automatically. We can’t adopt if we don’t want to have kids naturally, we can’t adopt as formerly incarcerated people, which sucks.”

While working in Oakland, fate intervened once more.

“Unfortunately, after my release from prison in Oakland, I was shot. I was shot in the right hip. The bullet hit my sciatic nerve and kind of destroyed my foot,” Anthony said.

This injury led to yet another drastic shift in Anthony’s life. He can no longer play basketball and has moved back to Southern California to be closer to his mom.

“I wanted to be closer to home because I’m a mama’s boy,” Anthony said. “I had to be close to my mom because I felt death.”

Back at his mother’s home in Compton, Shelly keeps the memories of Anthony’s past life in a box, tucked away in the den. Its contents spill over; dozens of letters from mother to son, photos of a young Anthony in a prison uniform, and a letter of commutation.

“Put that box up when you’re finished,” Shelly calls to her son, as he rifles through his memories.

The pair have been through hell and back. On the other side of 20-plus years of strife, they sit on the couch, surrounded by old family photos. They joke and laugh with each other, bickering in jest.

As they cuddle up to one another to have their photo taken, she gives her son a quick glance before the camera clicks.

Her boy is home.